I know a development team that's currently in arbitration with a sports club. The project was supposed to take four months. It took two years. The website still isn't live.

Both sides think they're the victim. Both sides are partially right. And the whole disaster was preventable from day one.

Here's the story, stripped of identifying details but otherwise exactly as it happened.

How It Started

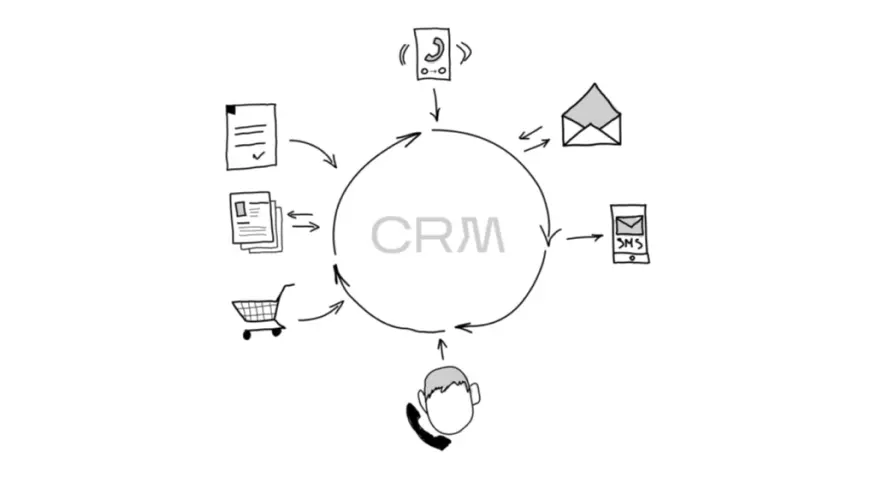

The sports club needed a new website. Their old one was built in 2015 and looked like it. They wanted something modern: ticket sales, merchandise store, member portal, news section, live match updates. Standard stuff for a club their size.

They found a development agency through a referral. Good portfolio. Reasonable prices. Nice people in the meetings. Everyone got along great.

The agency quoted a fixed price for "a modern club website with e-commerce functionality." The club said yes. Hands were shaken. No detailed specification was written.

This is where the bomb was planted.

The First Six Months

Development started. The agency built wireframes. The club's marketing director looked at them and said, "This isn't quite what I imagined."

Fair enough. Wireframes got revised. Then revised again. The marketing director showed the designs to the club president. The president had opinions. Different opinions from the marketing director. More revisions.

Three months in, they were still on wireframes.

The agency started getting nervous. They'd quoted based on a four-month timeline. But they didn't want to seem difficult, so they kept saying yes to changes. "We want to make sure you're happy."

By month six, actual development began. Sort of.

The Middle Period

Here's where it got ugly.

The club kept adding features. "Can the member portal also handle season ticket renewals?" "What about integration with our POS system at the stadium?" "We need the news section to pull from our social media automatically."

Each request seemed reasonable in isolation. The agency kept saying yes. Partially because they wanted to please the client. Partially because they had no document to point to that defined the original scope.

The development team worked weekends. Morale dropped. Two developers quit. The agency hired replacements who had to learn the codebase from scratch.

Month twelve arrived. The website was 60% complete. The club was furious about the delays. The agency was furious about the endless changes. Trust evaporated.

The Death Spiral

The club's board got involved. They demanded weekly progress meetings. These meetings became three-hour arguments about who promised what and when. Nobody had documentation to prove their position.

The agency tried to draw a line: "We'll finish what we've built, but new features need a separate contract." The club interpreted this as hostage-taking. "You're trying to charge us extra for what we already paid for."

The agency interpreted the club's behavior as scope creep. "You keep changing requirements without acknowledging it."

Month eighteen: The agency delivered what they considered a finished product. The club rejected it. "This isn't what we asked for."

Month twenty: Lawyers got involved.

Month twenty-four: Arbitration proceedings began.

The website, as of this writing, is still not live.

What Went Wrong

Every project failure is a combination of causes. But this one had three fatal problems that sealed its fate before development started:

No requirements document. When I say "no requirements," I mean there was literally nothing written down beyond the proposal. No user stories. No acceptance criteria. No feature list with priorities. The phrase "modern club website with e-commerce functionality" meant something different to every person involved.

No change management process. Changes happened in meetings, over email, in casual conversations. Nobody tracked them. Nobody assessed their impact on timeline or budget. Nobody got sign-off. When the project went sideways, neither side could reconstruct what had been agreed to.

A fixed price for undefined work. This is the financial version of writing a check to "cash." The agency locked themselves into a number before understanding the scope. The club assumed that number covered whatever they wanted. Both assumptions were wrong.

The Uncomfortable Truth

The agency blames the club for endless changes. They're not wrong—the requirements did keep expanding.

The club blames the agency for poor communication and slow delivery. They're not wrong either—professional development teams should force clarity, not just accept vague direction.

But here's the truth nobody wants to admit: both parties got what they incentivized.

The club incentivized flexibility by refusing to commit to specifications. They got flexibility—and chaos.

The agency incentivized accommodation by never pushing back on scope. They got a "nice" client relationship—until it exploded.

What Should Have Happened

A different version of this story exists. One where the project ships in five months and everyone's happy. Here's what it looks like:

Week one: Before any design work, a detailed requirements workshop. Every feature discussed, documented, and signed off. User stories written for each function. Acceptance criteria defined. This document becomes the contract's technical appendix.

Fixed scope, variable timeline (or vice versa). Either the agency commits to specific features with timeline flexibility, or they commit to a timeline with scope flexibility. Never both fixed. The project management triangle exists for a reason.

Change request protocol. Written into the contract: all changes require a formal request, impact assessment, cost adjustment, and sign-off before implementation. No exceptions. No "quick additions" that balloon into major features.

Milestone payments. 20% upfront. 30% at approved design completion. 30% at development completion. 20% after launch and acceptance period. Each milestone has specific, measurable deliverables.

A single decision-maker. Not a committee. Not "the board will review." One person from the club authorized to approve designs, accept deliverables, and sign off on changes. If that person isn't available, the project pauses.

The Modern Alternative

Sports clubs in 2026 have options that didn't exist five years ago. AI-powered development tools can generate functional code faster than traditional methods. This changes the economics.

A project that once required six developers for four months might now require three developers for two months, with AI handling routine code generation. The remaining humans focus on architecture, integration, and custom logic.

What does this mean for disaster prevention? Faster iteration. Lower cost of changes early in the process. More budget for proper requirements gathering. And critically: less financial pressure that causes agencies to agree to impossible terms just to win the contract.

The technology doesn't fix bad project management. But it does reduce the stakes of early mistakes and creates room for the process improvements that actually prevent disasters.

The Lesson for Both Sides

For clubs hiring developers: The cheapest quote usually isn't. Insist on a detailed specification before signing anything. Budget for requirements gathering as a separate phase. And accept that "we'll figure out the details later" is a recipe for arbitration.

For development teams: Stop saying yes to everything. Your job is to deliver working software, not to be agreeable in meetings. Push for specifications. Document changes religiously. And build the cost of scope uncertainty into your quotes.

The sports club is still without their website. The agency is still fighting for payment. Their lawyers are getting rich.

All of it was avoidable with a document that took a week to write.

The BrightByte builds digital platforms for sports organizations with clear processes that prevent disaster. We start every project with comprehensive requirements documentation, use AI-assisted development to reduce timelines, and maintain transparent change management throughout. If your club needs digital infrastructure built properly, reach out before you learn these lessons the expensive way.